This is the third post in a series by Meghan Rubenstein. Find her previous posts here.

With the archaeological field season over at Kabah, I shifted my focus to two other facets of my project: archival research and illustrations. For the next several months I traveled to museums, libraries, and archives in Mérida and Mexico City. I also returned frequently to Santa Elena and Kabah, where I continued to photograph the site and work on a series of drawings.

In order to study Kabah’s Terminal Classic architecture, I needed to collect as much data as possible to try to understand the buildings as they were over a thousand years ago. The documents of explorers, travelers, architects, and archaeologists proved essential, as they made it possible to trace how natural deterioration and human intervention have modified the site. I began the archival research a full year before leaving for Mexico. One of the most extensive archives of Precolumbian architecture, the George F. and Geraldine D. Andrews papers, is housed within the Alexander Architectural Archive at my home institution, the University of Texas at Austin. George Andrews (1918-2000), a practicing architect and a Professor at the University of Oregon, dedicated his life to recording Mesoamerican architecture, particularly in the Yucatán peninsula. Although the archive is still being processed [a number of documents are now digitized and available online], I was able to study his field notes and correspondence, as well as hundreds of photographs, negatives, and slides.

Andrews’ work at Kabah began in the 1960s, but the first modern documentation dates back to 1841, when explorers John Lloyd Stephens and Frederick Catherwood visited the site. Following their trip, a number of other individuals traveled to Kabah, including Désiré Charnay and Teobert Maler, who published their own images and descriptions. In the early 20th century, the National Institute of Archaeology and History (INAH) in Mexico started consolidation and restoration at Kabah, beginning the first large-scale excavation in the 1950s. Copies of the field reports for every project approved by INAH are available in their archives in Mexico City. My field work will also become part of this collection. In addition to the INAH reports, I found additional sources of information about Kabah in the university and museum libraries in Mexico City and Mérida, where I located several theses produced by students in Mexico.

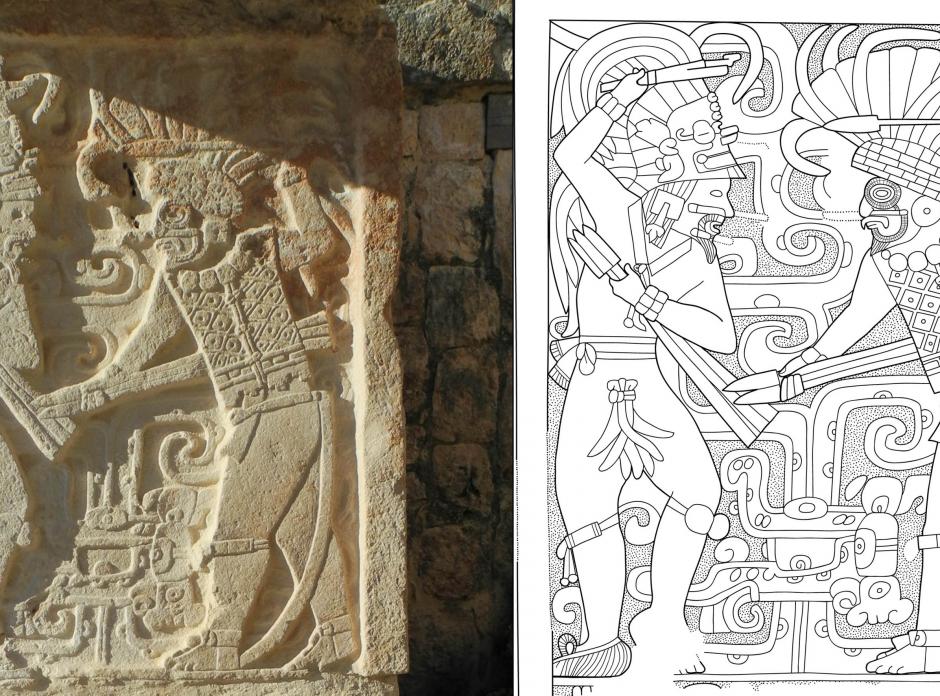

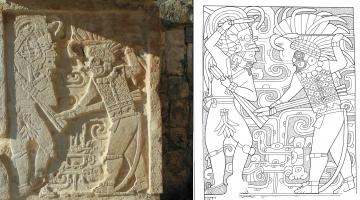

In addition to my written analysis, I wanted to add to this record by contributing new illustrations of the art at Kabah, specifically the site's carved doorjambs. There are two sculpted jambs on the Codz Pop, two in the American Museum of Natural History in New York, and four associated with the Manos Rojas. Illustrations clarify data that is not easily visible by translating it into a graphic format. More than a didactic tool, for me drawing is also a research tool. It takes hours, sometimes days, to produce a field sketch. Then, at home I create a digital drawing. Once I complete this version, I take a copy of the new drawing to the site to check it against the actual object. Finally, I return once more to the computer to modify the drawing based on any new observations. The countless hours of close looking make it possible to see the image more clearly the second or third (or fourth) time around.

While working in the archives was a quiet activity through which I could connect with past investigators at Kabah, drawing was a chance to interact with visitors to the site. My first drawings were of the doorjambs from Room 21 of the Codz Pop—one of the main attractions for tourists. As I was often standing in the doorway, conversations started easily. People from all over the world—and just down the road—would make an effort to communicate with me in either Spanish or English, even when neither was their native language. Tour guides asked me about the meaning of the building. Younger school kids wanted to know where I was from and how I got there. Older students were curious about my drawing technique. Custodians of the site would tell me what they thought about the images they have been looking at for decades.

Working in the archives and at Kabah also opened up new directions for my research. In the next post I will share how my final month in Mexico was spent planning my return.

This entry is part of a series by Meghan Rubenstein documenting her fieldwork in Mexico in 2012 and 2013. Because the entries are taken directly from her personal reports created in the field, they refer to the work being undertaken in the present tense.