After more than a year of planning, which included grant writing, interviews, and endless paperwork, my move to Mexico still managed to sneak up on me. Three weeks ago, I packed my bags and boarded a plane for Mérida. Thanks to the support of a Fulbright-García Robles grant, I will spend the next nine months in Mexico while I complete the fieldwork for my dissertation on Maya architecture in the Puuc region of Yucatán.

The Puuc region, which extends from the southern tip of the state of Yucatán into northern Campeche, is known for its Precolumbian architecture. Considered among the most spectacular in Mesoamerica, Mexicans and foreigners alike travel to see the intricately carved stone buildings. My research focuses on the mosaic facades, whose motifs reflect—and probably shaped—regional politics and religion, two inseparable aspects of ancient Maya culture.

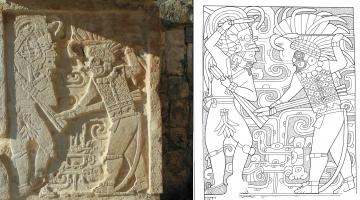

My current work narrows in on a 9th century structure at Kabah known as the Codz Pop. This building, which you can see above, is regularly referred to as the most baroque example of Maya architecture—as not a surface is left untouched. Yet as unique as it is, the Codz Pop still adheres to the Puuc style, suggesting that there was a prescribed balance between regional and local identity. My interest is what this relationship can tell us about the socio-political nature of the Terminal Classic period in the Puuc region (c. 800-1000 CE). While in Mexico, I will be collaborating with local scholars and working in several libraries and archives.

At our Fulbright orientation in Mexico City, just two weeks ago, we were cautioned not to worry if it took a month or more to adjust to Mexico and start our projects. Yet while I was still in Mexico City, I received an email from the archaeological project at Kabah that the current field season was ending mid-September. A few days later, I was back in Yucatán and on a bus heading south to Kabah, where I joined the team.

At the gate, I was waved in to find the director of the project, Lourdes Toscano Hernández, an Instituto Nacional de Antropología e Historia (INAH) archaeologist whom I had met during a preliminary visit the previous year. The first day was spent touring recent excavations and meeting the rest of the project members. The day went by quickly, and at 6:00 am the next morning I was outside my door in Santa Elena, a town 10 km north of the site, waiting for a ride back to Kabah.

Monday through Friday, and sometimes Saturday, we work until 9:00 am when breakfast is brought to the site from Santa Elena, where the project is stationed. By the time we finish eating, the sun is intense. If I haven’t done so already, I roll down my sleeves, apply another layer of sunscreen, and pull my hat over my ears. It is hot and just keeps getting hotter until 2:30 pm when we break for the day and return to the main project house for a late lunch.

My primary job at the site is to register stones from the façade of the Codz Pop, where about half of the team is currently working. The pieces might look like a mess, but I am quickly learning to recognize the ordered fall patterns, which can be used to understand not only the original structure, but also its collapse. Each stone is carefully excavated, mapped, and labeled with the coordinates of the 2 meter square in which it is found. I make a record of what parts we have and which are missing for each so-called “mask,” the most common motif. Then, the pieces are stored to the side and the excavation continues down another level.

Until the field season wraps up in a couple of weeks, I will continue to work alongside the project, both learning more about their objectives and sharing my own research plan.

This entry is part of a series by Meghan Rubenstein documenting her fieldwork in Mexico in 2012 and 2013. Because the entries are taken directly from her personal reports created in the field, they refer to the work being undertaken in the present tense.

This is the first post in a series by Meghan Rubenstein. Read her second post here.