The fascinating exhibit The Painted City: Art from Teotihuacan on view at LACMA [now closed], has made me think again about this magnificent city. As many as a quarter of a million people lived there at its peak in the 6th century C.E., some six or seven centuries after its initial settlement, making it one of the most populous cities in the world at that time.

It is located in the Teotihuacan Valley, a side pocket of the great Basin of Mexico, about 200 square miles of land to the northeast of the Basin, surrounded by hills. Many springs produced water for sustenance, and about half the land was suitable for farming. The metropolis covered 9 square miles and was fully occupied. There were at least 5,000 structures. There is a well-conceived grid plan oriented to 15 degrees 25 minutes east of true north, suggesting that the entire site was carefully planned. Several astronomical explanations have been advanced for its alignment, none entirely convincing.

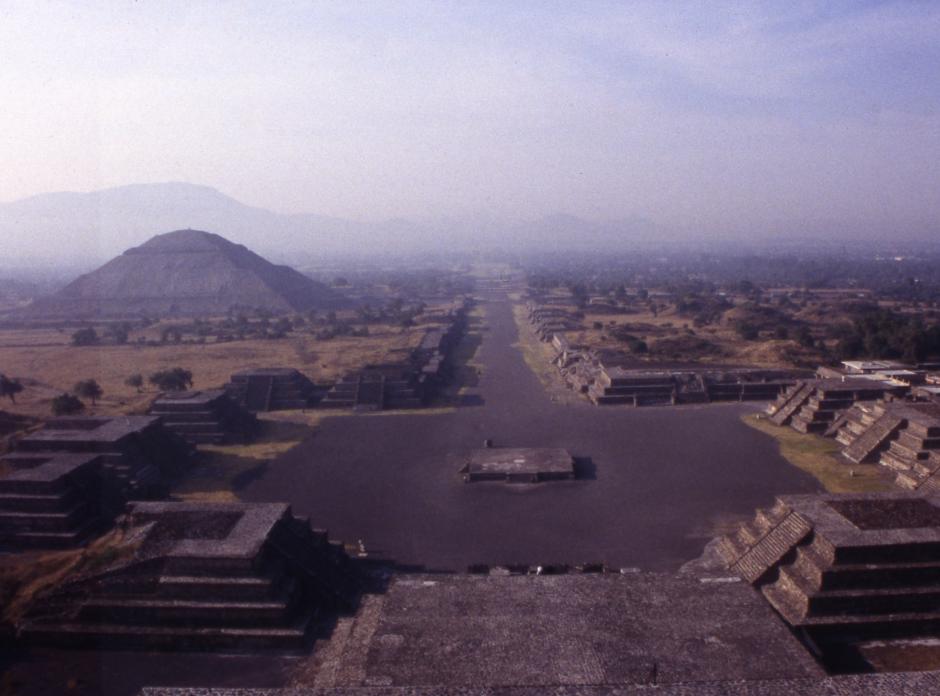

The main axis is the so-called Avenue of the Dead, which runs approximately north-south for 4 miles; another avenue runs east-west at right angles to the main axis. A royal palace sits at the center, fronting a great plaza. Teotihuacan was thus divided into quarters, like Tenochtitlan and many other 4-part altepetl or states of Postclassic (c. 1000-1500 C.E.) central Mexico.

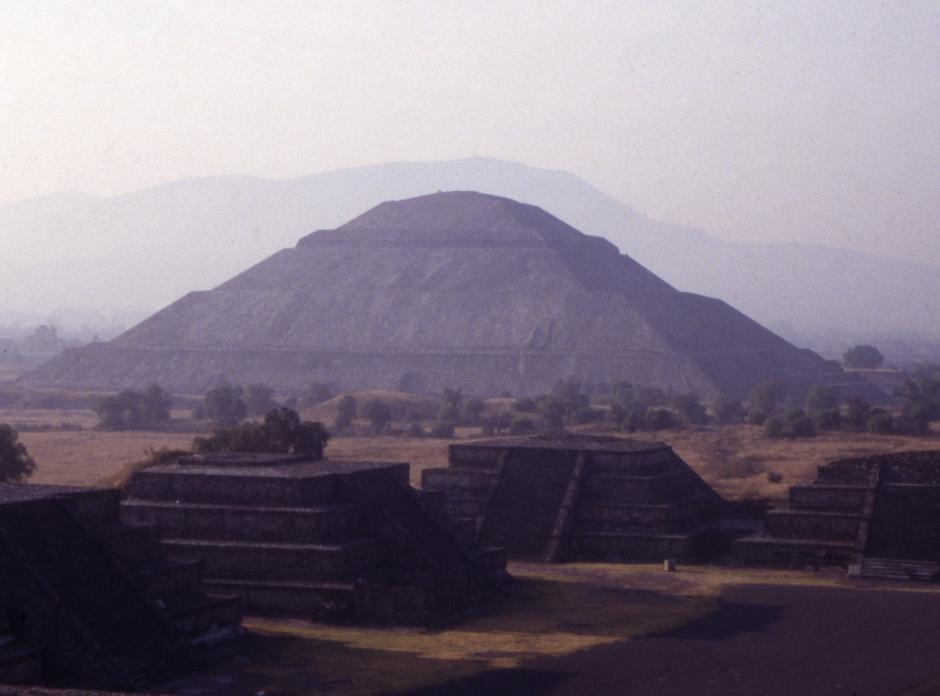

The most imposing and oldest structure is the Pyramid of the Sun, which can be seen from many miles away. Tunneling by archaeologists over the last several decades has revealed that construction was done mainly in the late formative period (around the time of Christ); laborers brought in more than a million cubic meters of adobe and stone rubble. In its final form it rises in four tiers to a 70-meter-high summit, crowned by a temple structure with a flat roof. Its base is 225 meters wide. It has a single stairway, and there was a temple on its summit. It faces west, looking onto the main avenue.

There are remains inside the Pyramid of the Sun (at the base) of an earlier structure, probably just as large. Archaeologists discovered in 1971 that the pyramid is built over a natural cave, which runs directly beneath the center of the pyramid for 100 meters and ends in an enlarged clover-leaf-shaped chamber; the cave was reached by a tunnel. Ceramic remains beneath the cave show that it was used from protoclassic until Aztec times. In Mesoamerican cosmology, caves were conceived of as symbolic wombs from which gods emerged, and entrances into the underworld. The ancient use of the cave predates the building of the pyramid, and it remained a ritual center even after it was built over. The cave must have been hidden from the Spaniards because there is no record of it in the colonial period.

The Pyramid of the Moon is situated at the northern end of the Avenue of the Dead. It is typical of Teotihuacan architecture: a rectangular, framed entablature above a sloping batter. The exteriors were covered with thick, white plaster, painted red or with polychrome scenes. It was built after the Pyramid of the Sun, at the beginning of the Classic period. Both the Pyramids of the Sun and Moon attest to the power of Teotihuacan leaders to organize massive labor drafts, especially considering that they did not have iron to cut large stones or beasts of burden to haul them.

The royal palace or Ciudadela (citadel) consists of a broad, sunken courtyard, with sides measuring 640 m. long, which contains at its center the temple of Quetzalcoatl, a four-sided, six-tiered stepped pyramid with relief figures of feathered serpents alternating with fire serpents (bearers of the sun on its daily journey). It was built in the early Classic period (c. 200-800 C.E.). The many smaller structures on the Avenue of the Dead were thought to be elaborate tombs, hence the name of the avenue, but in fact they are smaller temples with broad platform structures, like the Pyramids of the Moon and Sun. There are also palace compounds, where the lords of the city resided. One of the most magnificent palaces is the Quetzal-Butterfly palace near the Pyramid of the Moon. The complex consists of 45 single structure rooms, bordering four platforms, arranged around a central sunken patio. The patio was open to the sky. Many palaces contained magnificent painted frescoes on the walls.

The Teotihuacan Mapping Project revealed that the city also consisted of multiple modular, residential compounds contained within walls that ran for 50-60 meters on each side. These were wards that were based on kinship, ethnicity, or commercial specialization. It was a cosmopolitan city, attracting people from all over Mexico. There was a Oaxacan ward in the west, where Zapotecs worshipped their own deities; a ward in the east consisted of merchants from the lowland Veracruz and Maya areas. One residential compound contained 176 rooms, multiple alleys, 21 atria and 5 courtyards. The degree of urban concentration at Teotihuacan would not be approached again in Mesoamerica until Mexico-Tenochtitlan in the 15th century, right before the Spaniards arrived.

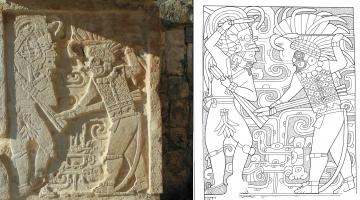

Teotihuacan had a tremendous influence on central Mexico and other parts of Mesoamerica in the Classic period. The city's ancient remains exhibit so many traits that we associate with Mesoamerica: the production of ceramics and obsidian in workshops, writing with glyphs, the use of bars and dots for counting with the vigesimal system, the development of the 260-day sacred calendar, a full pantheon of male and female deities, etc. Like Tenochtitlan in the 15th century, it may have depended as much on trade and tribute as it did on local agriculture. Elegant Teotihuacan ceramics are found in royal tombs all over Mexico at this time, even in distant Guatemala, at Tikal and many other sites. Despite Teotihuacan's giant footprint in the archaeological record of Mesoamerica, many questions remain. Who built the site? Did they speak Otomi or Nahuatl, or both, or other languages? The Mexica thought that Teotihuacan had been built by gods or giants.

The city declined in the early 8th century C.E. for reasons that remain unclear. There were signs of deliberate destruction, especially in the palaces and temples along the Avenue of the Dead. By that time, Teotihuacan's influence was no longer evident in other Mesoamerican sites. Refugees migrated to Atzcapotzalco and other places in the immediate area. Squatters occupied the site for at least 200 years after its destruction. Was Teotihuacan's demise related to the rise of Tula and the Toltecs? A major crisis rocked Mesoamerica in the 9th century. Was it due to environmental factors, such as drought? What caused the migration of so many peoples from the north, a movement that sent Uto-Aztecan speakers all the way down to Central America, to what is now Guatemala, El Salvador, and Nicaragua? Many Maya sites were overrun and abandoned in this period. Teotihuacan was the first major city to fall at the end of the Classic period.

How did the indigenous peoples of central Mexico remember the great city of Teotihuacan? Surely people who lived within sight of the giant pyramids in Postclassic, Colonial and post-Independence times did not need to wait until archaeologists in the 20th century to know about the sites that their distant ancestors had built. They must have cultivated oral traditions about the sacred, historic site. What are the earliest records of these memories? This is the subject of my next blog.