Peru is home to some of the richest seas on the planet. Today, over 10% of the entire world’s fish catch comes from the region. Yet, archaeologists are still untangling how ancient Andean civilizations utilized these bountiful sea resources to sustain large populations. Over the past four years, I have been excavating the 2,500 year old fishing town of Samanco to unravel how fisher folk contributed to early urban ways of life.

At first glance, the Andean coast looks like one of the least hospitable places for humans to live. This is one of the driest regions on earth, dotted with windswept mountain ranges and sand dunes. Ancient Andeans figured out a way to irrigate and bring water to the desolate landscape from high glaciers, and carve out an ecosystem viable for permanent human settlement. Fortunately for archaeologists, the arid qualities of the coastal landscape provide for excellent preservation.

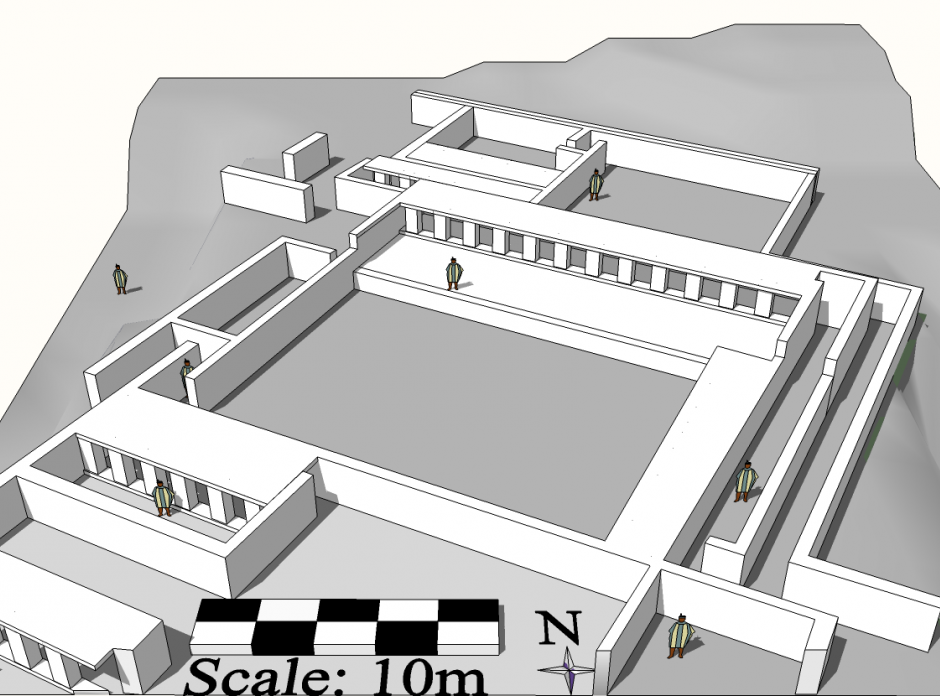

The ruins of stone buildings abandoned two millennia ago can still be seen from the surface at Samanco. Our team needed only to clear away rubble and sand to reveal an ancient town plan clustered into neighborhood compounds measuring over 100 acres. All around the structures are remnants of people’s daily lives: stone tools, clothing, pottery, fishing nets, and all sorts of food remains. Comparing architecture and material remains from these residential compounds gives us the opportunity to piece together occupation density, duration, types of activities, and even enable us to infer how society was ordered. Most importantly, we gain a glimpse into what life was like for people completely lost to history, as ancient Andeans did not leave written records. Moreover, archaeologists often focus on rich tombs or the highest segments of society, leaving the story of common peoples’ everyday lives untold.

Everyday life at Samanco revolved around communal patios which formed the heart of residential complexes. These patios, many of which could have comfortably housed over one hundred people, were completely surrounded by smaller rooms where people resided. All paths between different rooms lead to and from the patio. The patios were built with encircling platforms lined with columns which provided shaded areas for people to conduct everyday social activities such as food processing, eating, weaving, tool-making, and various other activities which bound the neighborhood together. Adjacent to one particular patio, we documented a kitchen with permanent hearths probably used for communal meals in the patios. People even buried their dead beneath the patios, preferring to keep them close to home.

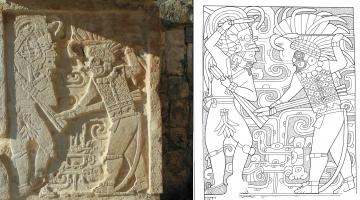

By far the most common materials encountered on-site are shells and fish bones, which indicated the centrality of the sea to everyday life. To give an idea of quantity, we analyzed over half a ton of shells and 30,000 fish bones recovered in and around Samanco’s residential compounds. The types of fish ancient Samanqueños caught varied from as small as sardines to as large as sharks and mahi-mahi. All of these were caught using basic reed boats, known as caballitos de totora, which resemble small kayaks. Most fish were caught with curtain nets, which stretch between two or more people and are similar to a tennis net. Later Andean cultures, like the Moche and Chimú, immortalized this type of fishing through vivid iconographic accounts on pottery and textiles.

The surplus of seafood likely provided Samanco with considerable power through the ability to trade with inland towns in need of protein-rich foods. Excavations at surrounding sites reveal that people did rely heavily on sea trade, long before centralized states and empires like the Inka created resource routes and networks. Yet, a perplexing question for us was how people could have moved large amounts of seafood. The ancient Americas did not have the beasts of burden which Old World civilizations relied so heavily upon. At Samanco, the possible answer to this question came from a stone building with uncharacteristically thick walls and symmetrical rooms, where our excavations revealed a corral used to house llamas. Llamas, once thought to only be able to survive in the high Andes, may have existed for millennia along the coastline. I believe they were used at Samanco as caravans to move seafood and other goods throughout the area, but our team is still working on this.

Despite not often being represented in popular media, ancient residences provide archaeologists with a treasure trove of information to understand the past. In many ways, they provide a much clearer picture of life for the majority of people often overwritten in history in favor of rulers and tiny segments of society. In this case, excavations of residences at a 2,500 year old town provide an intriguing view into early neighborhoods and seaside ways of life. In my next entry, I’ll bring a behind-the-scenes view into how we turned piles of artifacts and rubble from Samanco into our interpretations of the past.