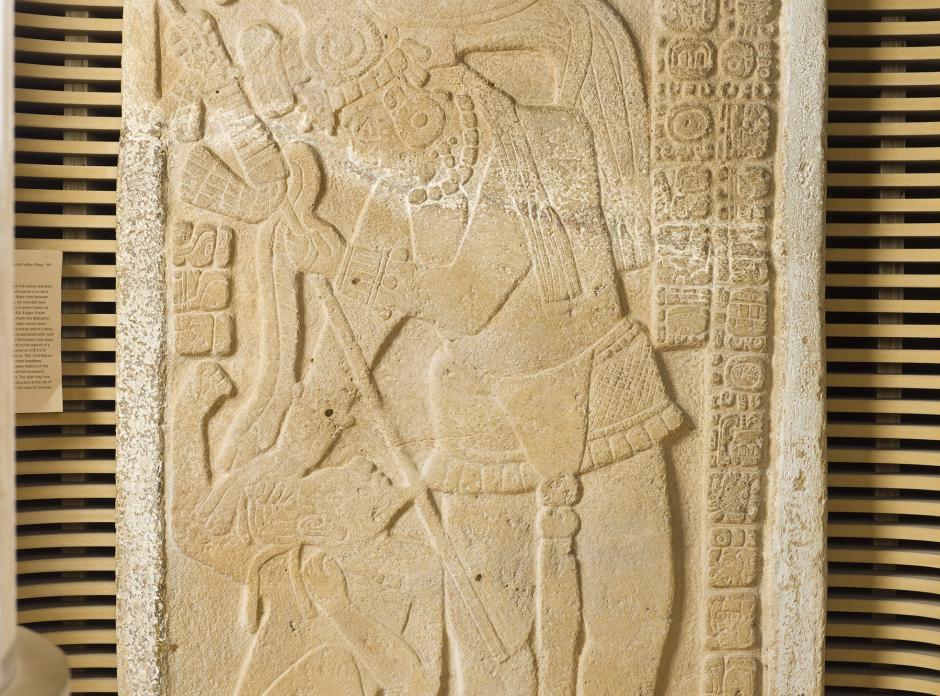

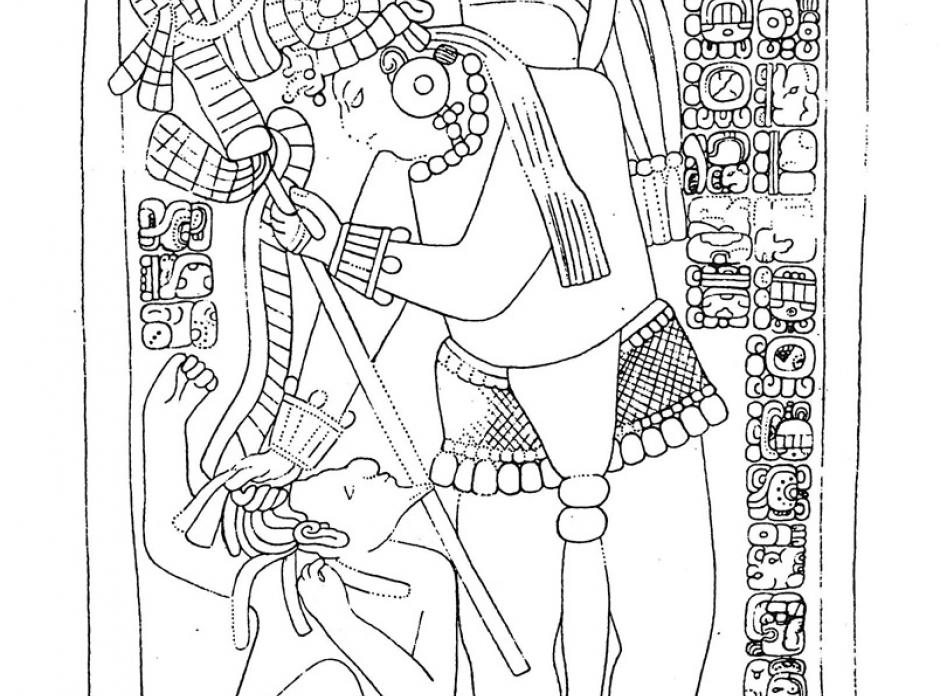

On loan and currently on view in the Ancient American art galleries at LACMA is a small but remarkable stela, a carved standing stone dedicated in AD 795, by the ruler of a small Maya kingdom in Chiapas known today as La Mar. Dryly called La Mar Stela 3 by scholars, the monument depicts a single warrior decked out in his finery: a necklace, ear ornaments and bracelets of jade, a finely woven kilt and loincloth, and well-made sandals. He is crowned with a deer head-dress crested by what were surely the blue-green feathers of the quetzal bird, a prized symbol of high social status across Mesoamerica. Clutching a spear in his left hand, with his right hand the lord of La Mar tightly grips the loose hair of a noble captive, a bearded warrior who has been stripped of his regalia and reduced to a cringing, animalistic figure.

The protagonist of Stela 3 is named in the right hand column of glyphs. Epigraphers, those who are expert in the decipherment of ancient Maya writing, often refer to this nobleman as “Parrot Chahk.” This gloss refers to the most obvious component glyphs in his name which include a macaw (read Mo’) and the rain-god “Chahk.” In other inscriptions where this same individual is mentioned his name seems more complicated and resists a full reading, but the legible Mo’ Chahk suggest an avian aspect of the rain-god. The seated captive is a lord from the kingdom of Pomona and, according to epigrapher Marc Zender, bears the moniker Aj K’esem Took’.

In and of themselves, the image and text are stark and simple: captor and captive, apparently in the aftermath of some combat that has not gone well for the seated and wriggling prisoner. But if we take those figures and brief inscription and reconnect them with related objects from La Mar and the great dynastic capital of Piedras Negras, Guatemala, a far richer story emerges. La Mar Stela 3 offers a critical peek into the political landscape of Maya kingdoms in the 8th century AD, telling us about warfare and courtly life.

Because this stela was not found by archaeologists, and no pictures or descriptions are known of its find site, some important pieces of context, and the meaning that such context provides, are forever lost to us. Did the monument once stand in front of a temple? Was it incorporated into a palace? Might it have been part of a suite of sculptural work that told a broader story? We may never know.

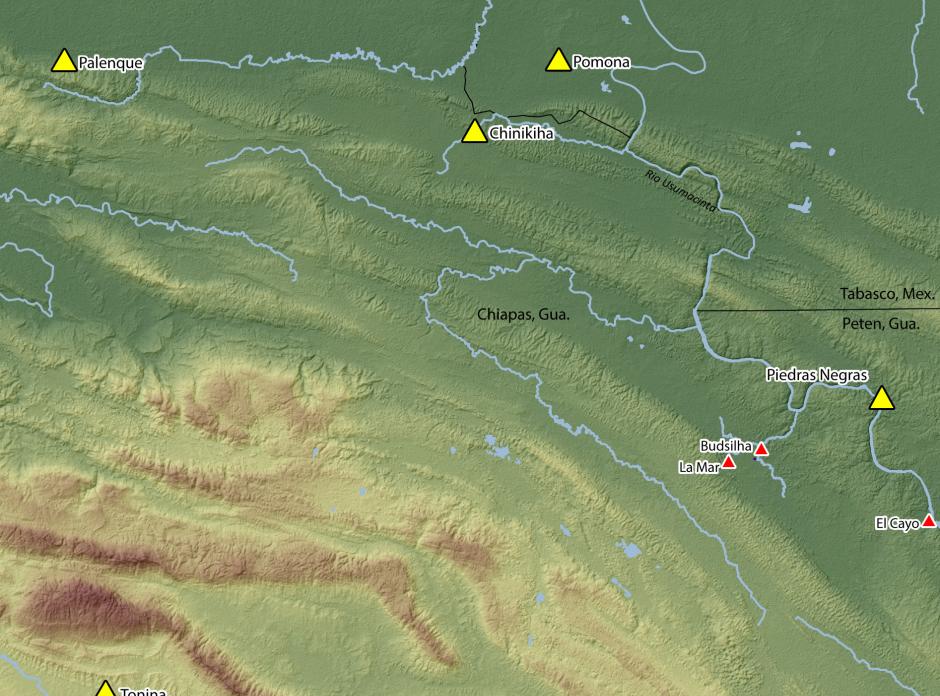

We can, however, securely deduce that it comes from the archaeological site of La Mar, Chiapas, Mexico. Little is known archaeologically about La Mar, despite the fame of its monuments. The site was first brought to the attention of modern scholars by the Austrian explorer, photographer and archaeologist Teobert Maler. In 1897, Maler was taken to visit a ruin located in the agricultural fields surrounding a logging camp called La Mar, a name which he then applied to the ancient city. No formal research was undertaken at the site for the next century.

However, research that we have conducted with colleagues and local collaborators in and around La Mar since 2010 has revealed a long history of occupation for this relatively small center, extending from at least 250 BC to AD 800. La Mar benefited economically from its position as on an important north-south transportation route between the Mayan highlands to the south and the plains of Tabasco to the north, but it was also precariously located on the main road between the warring dynastic powerhouses of Tonina (43 miles to the southwest), Piedras Negras (10 miles to the east), and Palenque (50 miles to the northwest). Our research has documented the many defensive walls that dot the landscape around the site and provide material evidence for the conflicts recorded in inscriptions from Tonina, Palenque and Piedras Negras, which name captives and military allies from La Mar.

Maler’s description of the site is rather thin, but in addition to two small pyramids and some adjacent buildings, he found two broken stelae. Now designated La Mar Stela 1 and Stela 2, and housed in museums in Mexico, they depict the rulers of this small center and their courtiers. It is Stela 1, in particular, that reveals the significance of the monument now on view at LACMA. Here, in the upper fragment, Parrot Chahk is depicted in AD 783, having acceded to rulership at La Mar at the age of forty-five.

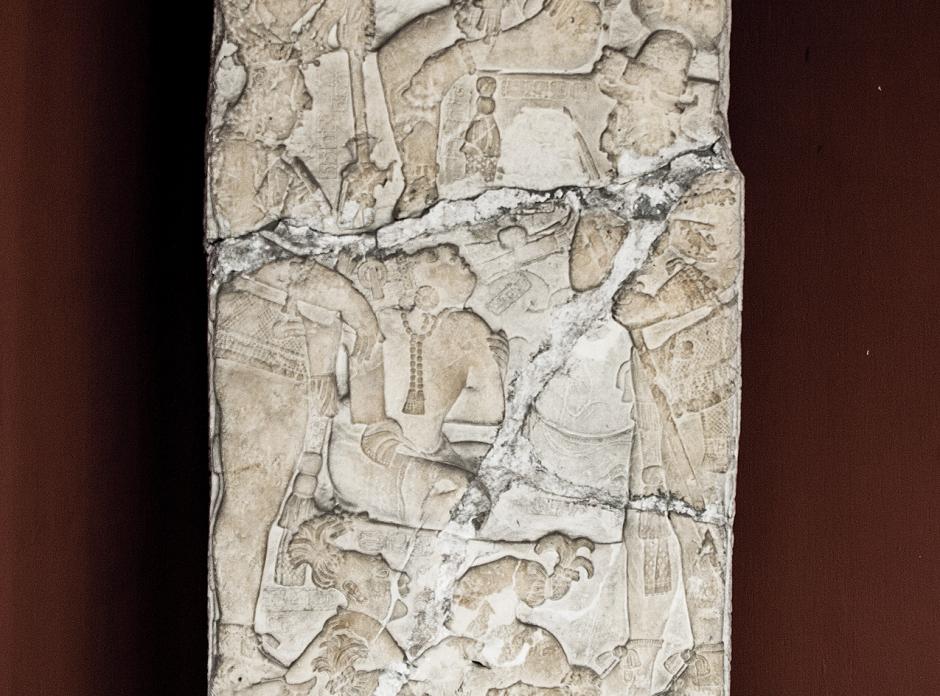

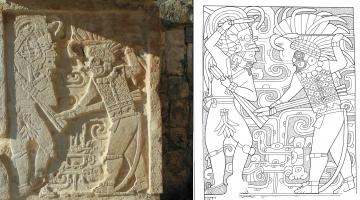

Though a petty king in his own right, Parrot Chahk was nonetheless a vassal and ally of the rulers of the great dynastic center of Piedras Negras. At Piedras Negras, Parrot Chahk is shown on monuments as a youth in the court of his overlord. As an adult, he was such an important courtier that his name appears inscribed on the royal throne. But to fully understand the story told by La Mar Stela 3, we must turn to Stela 12 from Piedras Negras, where Parrot Chahk is shown as a victorious warrior.

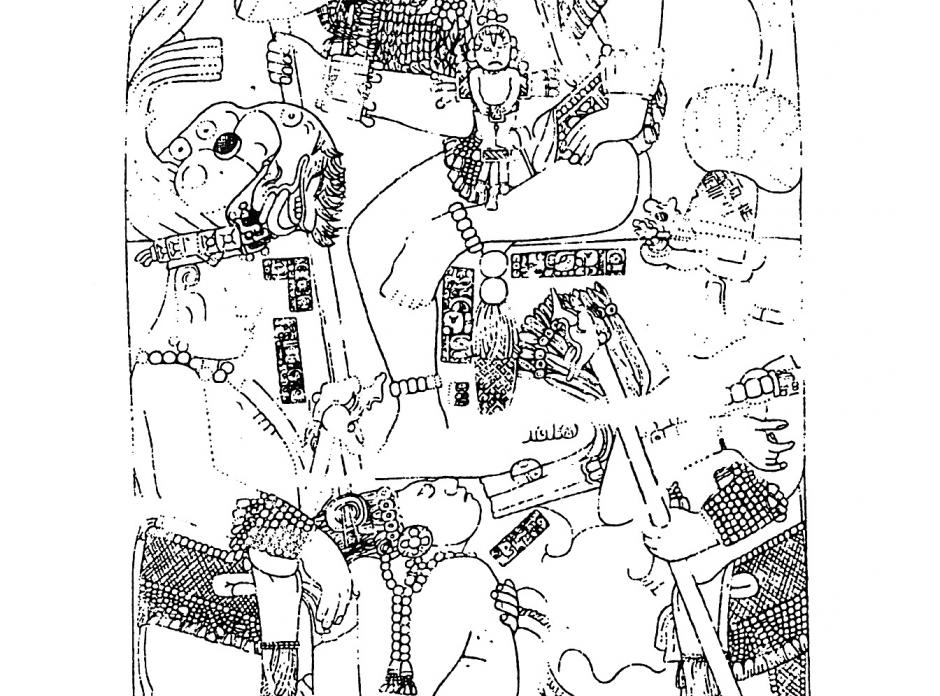

Stela 12 depicts the last known ruler of Piedras Negras in the afterglow of a great victory over the neighboring kingdom of Pomona, Mexico in AD 795. The king is enthroned at the top of the scene, flanked by his standing warlords to left and right. The standing figure on the left of the scene from Stela 12 is clearly named “Parrot Chahk, He of 10 captives, ajaw [lord] of the Rabbit Stone place, bakab [a lordly title].” This is the very same man named on La Mar Stela 1 and the on view Stela.

Indeed, on the monument from Piedras Negras he is decked out in the very same regalia he wears on La Mar Stela 3, including his feathered deer head-dress. Arrayed below the triumphant figures are the bound and cowering captives from Pomona’s defeated forces, awaiting their fate. The implication of the text and imagery is that the king of Piedras Negras, with perhaps a little bit of help from his friends, has won a victory in battle over his foes.

Among the captives, however, seated and bound with rope at the bottom right of the scene on Piedras Negras Stela 12 is a bearded figure. His face looks upward, and his name is clearly inscribed in his shoulder, Aj K’esem Took’. This is the very same bearded captive name on the stela at LACMA, identified by his name and his (for the Classic period Maya) unusually robust facial hair.

By juxtaposing Stela 3 from La Mar and Stela 12 from Piedras Negras we have an interesting tweak to the royal propaganda. Stela 12 would have us believe that the Piedras Negras king is the victorious war leader who has accumulated the captives from Pomona. Stela 3, however, reveals a more complete truth: Parrot Chahk was the warrior who captured Aj K’esem Took’, and then several days later delivered him – and perhaps the other prisoners – to his Piedras Negras overlord. Did the king of Piedras Negras go to battle himself? Or did he rely entirely on courtiers, warlords and vassals to do the dirty work? We may never know, but La Mar Stela 3 certainly complicates the royal headlines.

Finally, the connection between La Mar Stela 3 and Piedras Negras Stela 12 confirms one more important piece of information that expands our vision of the ancient political landscape. Lords and captives named in the inscriptions of at least three of the great Maya capitals – Tonina, Palenque and Piedras Negras – are said to be from a place called “Rabbit Stone” by scholars (the name could perhaps be read Pe’tuun). Parrot Chahk is explicitly named as lord of the Rabbit Stone place on Piedras Negras Stela 12, and he is undoubtedly shown on La Mar Stela 1 acceding to rulership there. Thus, by connecting the monument currently on view in the musuem to La Mar Stela 1 and Piedras Negras Stela 12 we can say rather securely that the former comes originally from La Mar, and that La Mar was indeed the “Rabbit Stone” place.

Acknowledgements:

Our thanks to Dr. Marc Zender, Dr. Stephen Houston, and Dr. Simon Martin who generously provided feedback and corrections concerning the epigraphic data in this post. Any errors of fact or interpretation are entirely our own.

Sources and Further Reading:

Golden, Charles. 2010. Frayed at the Edges: Collective Memory and History on the Borders of Classic Maya Polities Ancient Mesoamerica 21: 373-384.

Houston, Stephen D. 2004. The Acropolis of Piedras Negras: Portrait of a Court System. In Courtly Art of the Ancient Maya. M. Miller and S. Martin, eds. Pp. 271-276. Thames and Hudson, New York.

Houston, Stephen, Héctor Escobedo, Mark Child, Charles Golden, Richard Terry, and David Webster. 2000. In the Land of the Turtle Lords: Archaeological Investigations at Piedras Negras, Guatemala, 2000. Mexicon 22(5):97-110.

Maler, Teobert. 1903. Researches in the Central Portion of the Usumatcintla Valley. Memoirs of the Peabody Museum of American Archaeology and Ethnology, Vol. 2, No. 2. Cambridge: Harvard University.

Martin, Simon, and Nikolai Grube. 2008. Chronicle of the Maya Kings and Queens. New York: Thames and Hudson.

Schele, Linda, and Nikolai Grube. 1994. Notes on the Chronology of Piedras Negras Stela 12. Texas Notes on Precolumbian Art, Writing, and Culture 70:1-4. http://repositories.lib.utexas.edu/handle/2152/16104

Scherer, Andrew K. and Charles Golden. 2012. Revisiting Maler’s Usumacinta: Recent Archaeological Investigations in Chiapas, Mexico. Precolumbia Mesoweb Monograph 1. Precolumbia Mesoweb Press, San Francisco.

Scherer, Andrew K. and C. Golden. 2014. War in the West: History, Landscape, and Classic Maya Conflict. In Embattled Places, Embattled Bodies: War In Pre-Columbian America, A. K. Scherer and J. W. Verano, eds. Pp. 57-87. Dumbarton Oaks Research Library and Collection, Washington, DC.

Zender, Marc. 2002. The Toponyms of El Cayo, Piedras Negras, and La Mar. In Heart of Creation: The Mesoamerican World and the Legacy of Linda Schele. A. Stone, ed. Pp. 166-185. Tuscaloosa: University of Alabama Press